Changanacherrensis et aliarum (1959.01.10): Oriental Ornament for a Conciliar Revolution

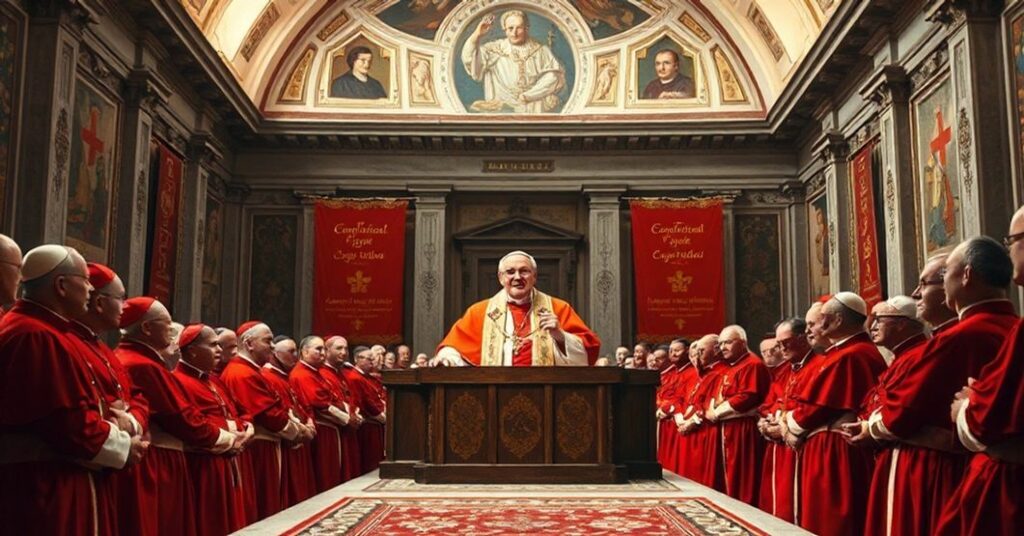

Regnum caelorum is invoked, missionary expansion is praised, and in polished curial Latin the text informs us that the eparchy of Changanacherry (Changanacherrensis) of the Syro-Malabar rite is elevated to a metropolitan archdiocese and made the head of a new ecclesiastical province, with Palai and Kottayam as suffragans; the archbishop gains the use of the pallium and certain ceremonial privileges, and the whole is clothed with the solemn formulae of perpetuity and canonical efficacy under John XXIII.