Grata recordatio (1959.09.26)

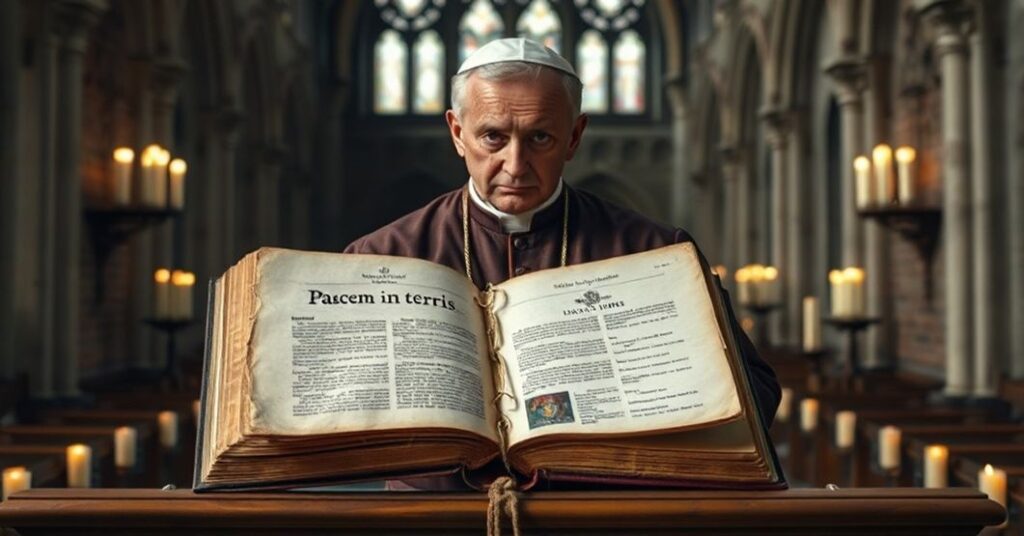

The document “Grata recordatio” (26 September 1959), issued by the usurper John XXIII, superficially exhorts the clergy and faithful to the devout recitation of the Marian Rosary in October, recalls with sentiment the encyclicals of Leo XIII on the Rosary, commemorates Pius XII, underscores the alleged continuity of the Roman pontificate, invites prayer for peace among nations and for rulers, warns in generic terms against “laicism” and “materialism,” and asks special prayers for the Roman Synod and the coming “ecumenical council.” Its sweetened Marian and pacifist rhetoric, however, serves as a cosmetic veil for the preparation of a revolutionary project that will mutilate the Kingship of Christ, relativize immutable doctrine, and inaugurate the conciliar sect.