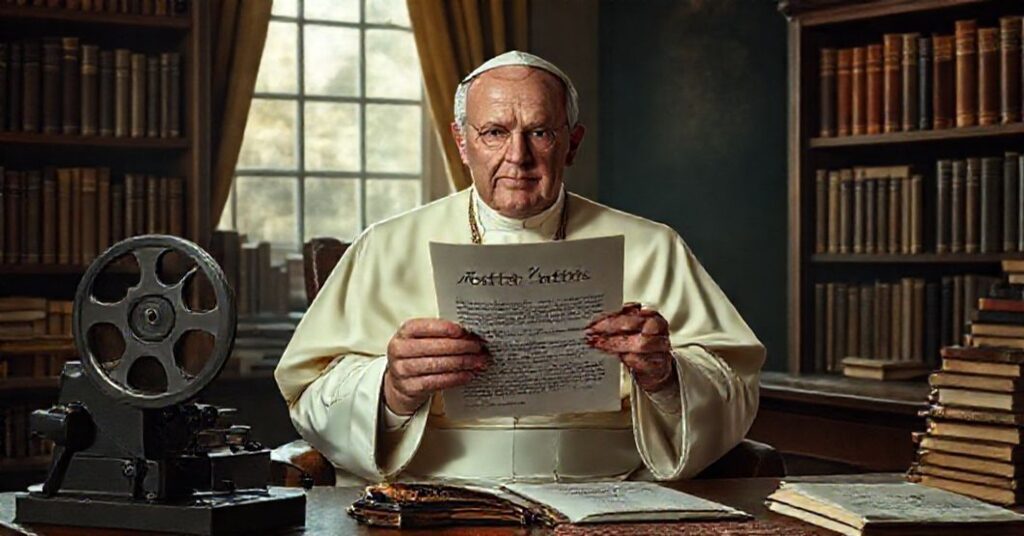

In this Latin letter of 29 June 1961, John XXIII addresses Martin John O’Connor, head of the Pontifical Council for Cinema, Radio and Television, on the 25th anniversary of Pius XI’s Vigilanti cura. He praises Pius XI’s concern for cinema, recalls the moral dangers of film (especially for youth), notes ecclesiastical initiatives to promote morally acceptable productions, commends national and international Catholic film organizations, and exhorts continued efforts so that cinema may serve education, culture, and “honest entertainment” under the guidance of competent ecclesiastical authorities. The entire text maintains a tone of pastoral encouragement toward collaboration with modern media and confidence that Catholic structures can elevate cinematic art for the moral and cultural benefit of society.

This apparently pious exhortation, however, is a paradigmatic document of the conciliar revolution: it subtly subordinates the supernatural mission of the Church to the naturalistic cult of culture, entertainment, and dialogue with the world, replacing the Kingship of Christ with managerial optimism about poisoned instruments that are objectively vehicles of apostasy.