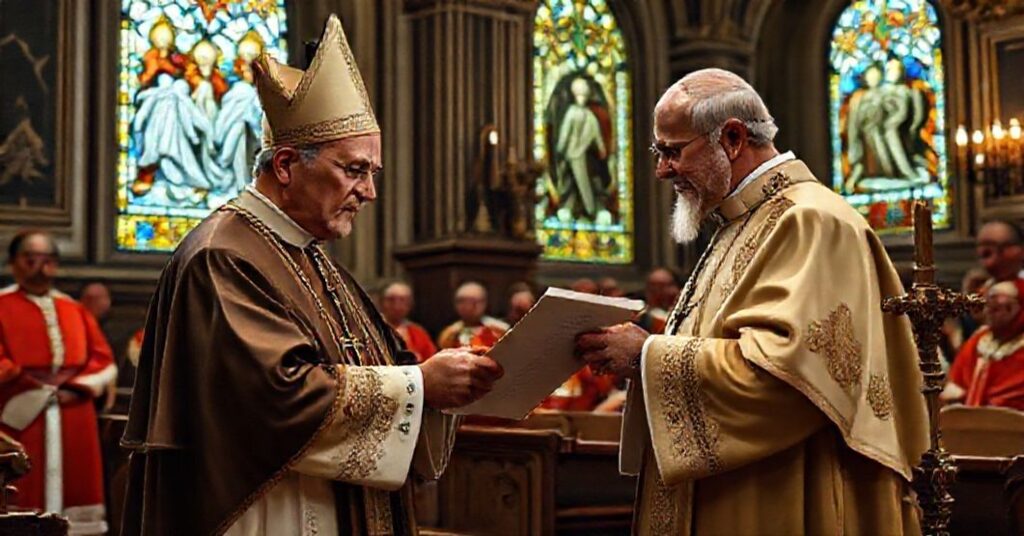

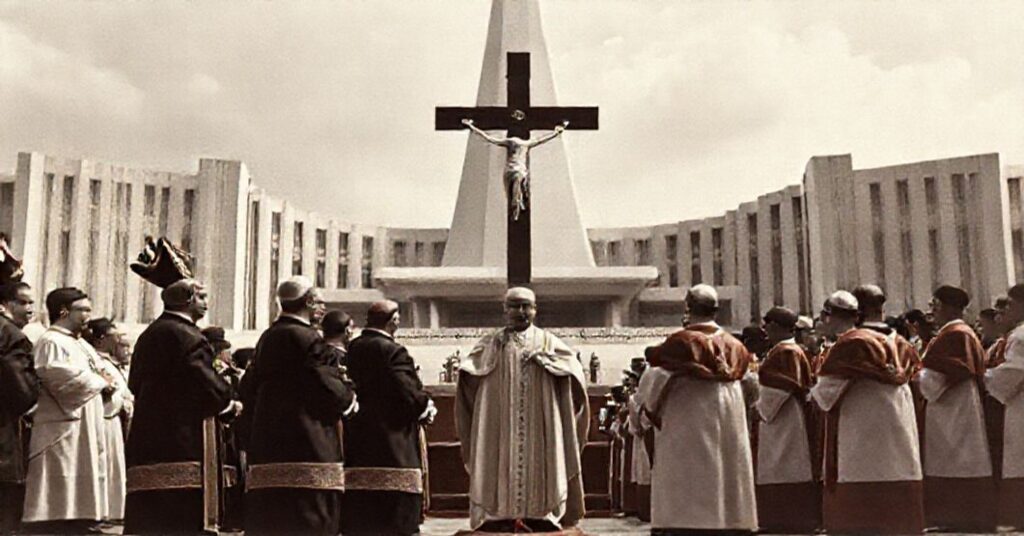

The Latin letter under consideration is a brief missive of John XXIII, appointing Manuel Gonçalves Cerejeira as his legate for the inauguration and “dedication” of the newly built Brazilian capital, Brasília. It praises Brazil for wishing to surround this political project with sacred ceremonies, urges that the new city become a beacon of “Christian humanism,” concord, justice, hospitality, festivity, and peace, and confers an “apostolic blessing” upon the celebrations. It is a polished, optimistic benediction of a modern state-capital, couched in religious language yet wholly subordinate to secular categories. In reality, this document is a concise manifesto of naturalistic civic religion, revealing the nascent conciliar sect’s abdication of the Kingship of Christ and its willingness to anoint the emerging Masonic world-order.