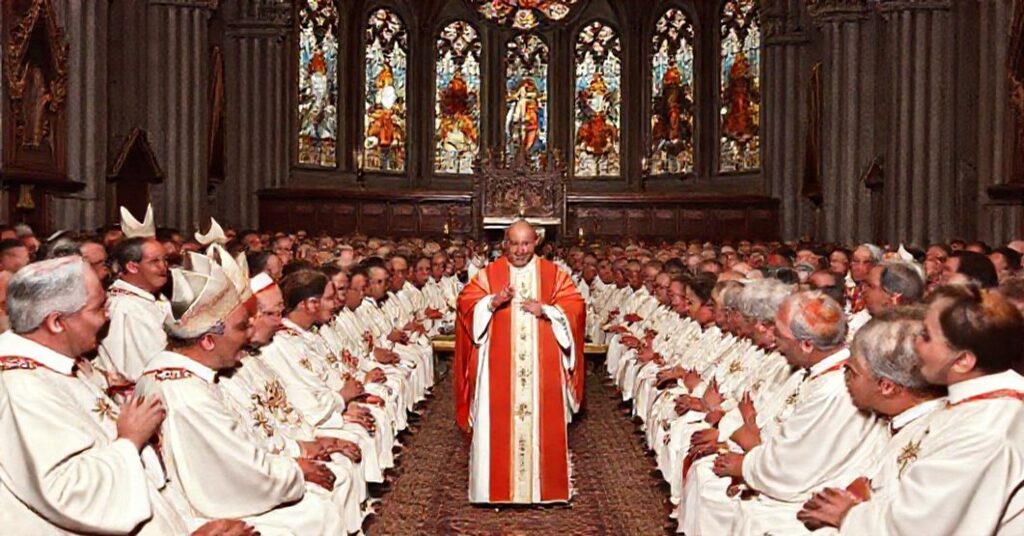

Iucunda laudatio (1961.12.08)

This Latin letter of John XXIII, addressed to Hyginus Anglés on the 50th anniversary of the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music, is an ornate panegyric: it praises the Institute as heir and guardian of sacred music, recalls Pius X’s reform and the chirograph “Tra le sollecitudini,” extols Gregorian chant, polyphony, Latin in the solemn liturgy, scholae cantorum, and even mentions adapting music in mission territories by elevating indigenous melodies for Catholic worship; the whole text wraps itself in traditional terminology to present the Institute as exemplary servant of divine worship under the aegis of the conciliar renovator.