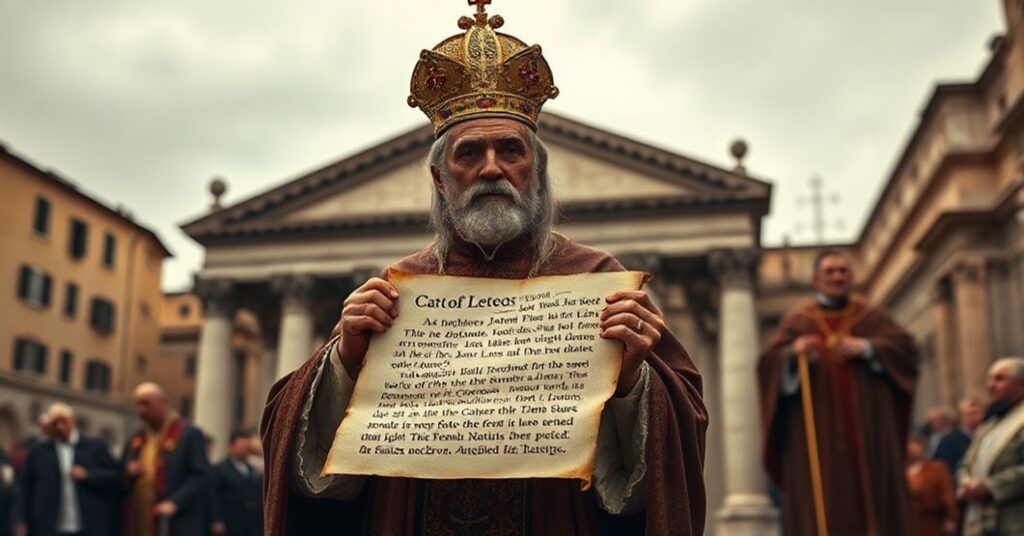

Mater et magistra (1961.05.15)

The document published under the name “Mater et Magistra” (15 May 1961) presents itself as a continuation and development of Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum, Pius XI’s Quadragesimo Anno, and the social teaching of Pius XII. It offers a lengthy treatment of economic modernization, “socialization,” state intervention, workers’ rights, agricultural policy, international aid, demographic growth, and global cooperation, framed as an adaptation of Christian social principles to contemporary conditions. It lauds scientific-technical progress, proposes a globalist conception of social justice between nations, promotes an enlarged role for public authorities, and systematically prepares the conceptual ground for the later conciliar agenda of “reading the signs of the times” and restructuring society through dialogue and development. In doing so, it subtly but decisively replaces the supernatural, hierarchical, and confessional order of Christ the King with a horizontal project of humanitarian, democratic, technocratic “Christian” social reform.