At the close of the first session of Vatican II on 7 December 1962, John XXIII addresses the assembled council fathers in Saint Peter’s Basilica. He congratulates them for their work, praises the “spectacle” of the gathered hierarchy, emphasizes unity, optimism, Marian devotion, and expresses the hope that the Council will make the Gospel more widely known and effective in modern civil life. He presents the Council’s purpose as adapting the expression of faith and morals so that Christ’s message may penetrate “every area of civil culture” and thanks the bishops for their collaboration with him in this project.

The Conciliar Spectacle and the Eclipse of the Catholic Religion

From Apostolic Authority to Sentimental Pageantry

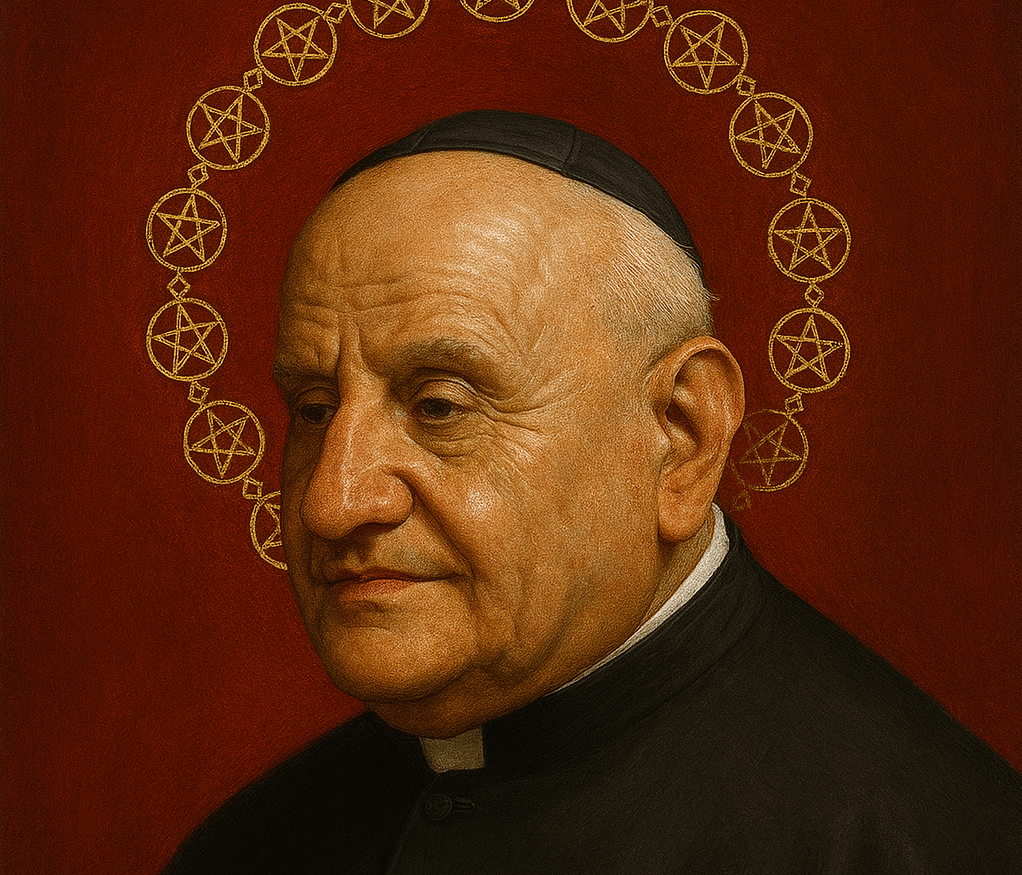

Already in this short allocution the entire conciliar revolution is visible in miniature. The man John XXIII, first in the line of usurpers, stands before the world not as a defender of the depositum fidei (deposit of faith), but as impresario of a new religious spectacle.

He does not remind the bishops that their first and grave duty is to guard the flock against error (vigilare in doctrina), to condemn the dominant heresies of the age, or to reaffirm the dogmatic condemnations of the authentic Magisterium. Instead, he exults in the image, in the optics, in the emotional impression made upon the world:

“We must rejoice in the spectacle which, in this great assembly, the one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church has offered to the world.”

The same term “spectacle” recurs for the torchlight procession:

“Our eyes were deeply moved at the remarkable procession of yours, which shone like a flame in the square of Peter.”

A true Roman Pontiff, formed by Trent and Vatican I, would tremble to describe the solemn gathering of bishops primarily as a “spectacle” for the world. Pius IX, in the Syllabus Errorum, condemns the liberal dream of a Church courting the world’s gaze and approval, rejecting the thesis that the Church must “reconcile herself… with progress, liberalism and modern civilization” (prop. 80). Pius XI in Quas primas recalls that the root of modern calamity is precisely the exclusion of Christ’s kingship from public life. But the tone here is the opposite: aesthetic triumph, public choreography, televised emotion. The shepherds are invited to contemplate how impressive they look.

This is not accidental vocabulary. It manifests a shift from the supernatural seriousness of a dogmatic council—called to define, to judge, to anathematize—to a theatrical manifestation of institutional self-celebration. The conciliar sect will repeat this pattern endlessly: gatherings, gestures, “ecclesial events,” while doctrine is softened, discipline dissolved, and the Most Holy Sacrifice displaced by horizontal assemblies.

Naturalistic Optimism and the Silencing of Judgment

On the factual level, John XXIII describes the Council’s aim thus:

“[Our ministry] has no other object, holds nothing more dear, than that the Gospel of Christ may be more and more known by the people of our time, put into practice, and that it may penetrate with sure step into every area of civil culture.”

At first hearing, this sounds harmless—even pious. But examined in light of integral Catholic doctrine, it is a textbook instance of modernist naturalism and ambiguity.

1. There is no mention of:

– the necessity of supernatural faith for salvation;

– the obligation of all nations to submit to the social kingship of Christ;

– the danger of heresy, indifferentism, Freemasonry, socialism, and laicism so forcefully condemned by Pius IX, Leo XIII, St. Pius X, Pius XI, Pius XII;

– the Four Last Things: death, judgment, heaven, hell;

– the centrality of the Most Holy Sacrifice of the Mass as propitiatory atonement for sins;

– the state of grace as the necessary condition for “putting the Gospel into practice.”

2. The Council’s purpose is minimized to a horizontal program: making the Gospel “known,” “implemented,” and diffused into “civil culture.” This is the vocabulary of religious sociology, not of the Church Militant.

3. The decisive omission is doctrinal combat. No hint appears that the bishops are gathered to condemn errors. Contrast St. Pius X, who in Lamentabili sane exitu and Pascendi identifies Modernism as the “synthesis of all heresies” and imposes condemnations and oaths. Here, precisely at the historical moment when Modernism rises again with renewed strength, the man on the throne proclaims serene optimism and compliments.

Silence here is not a neutral rhetorical choice. Silence about modernist apostasy, about Freemasonry’s war on the Church, about the duty of states to recognize the true religion, is complicity. The Syllabus explicitly unmasks the secularist program, yet the speech honors “civil culture” as terrain to be gently permeated, not as a rebellion to be judged and corrected.

This naturalistic optimism is the spiritual DNA of the “Church of the New Advent”: the Gospel reduced to an inspirational resource for democracy and culture, stripped of its juridical, dogmatic, and exclusive claims.

Linguistic Symptoms of Doctrinal Decomposition

The rhetoric of this allocution is revealing. It is suffused with:

– sentimental expressions: “singular joy,” “tender gratitude,” “fraternal unity”;

– vague euphemisms: “work of very great magnitude,” “pastoral solicitude,” “civilization”;

– rhetoric of expectation and “hope” from “all Catholics,” as if the Church’s task were to answer worldly expectations.

Notably absent is the precise language of Catholic dogma: sin, error, penance, sacrifice, conversion to the one true Church, submission to the Roman Pontiff as defined by Vatican I (*Pastor aeternus*), condemnation of heresy and false religions. Even when he pronounces the four marks—“one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church”—they function as decorative labels attached to an already redefined organism whose practical mission is to dialogically insinuate itself into modernity.

The repeated focus on the “spectacle” offered to the world manifests a shift from *veritas* to *imago*. The allocution exalts the visual and emotional unity of the bishops more than their duty to teach infallibly what was “believed always, everywhere, and by all” (*quod ubique, quod semper, quod ab omnibus*, St. Vincent of Lérins). This theatrical language prefigures the later cult of media events, papal “world tours,” and ecumenical shows replacing doctrinal firmness.

Such vocabulary is not accidental style; it is a pastoral strategy expressing a new theology: the Church as sacrament of world unity, not as Ark separating truth from error.

Theological Deviations: Council as Instrument of Adaptation

John XXIII describes the Council’s labors in terms of “studies and formulas regarding faith and morals” devised so as to achieve the end for which the Council was convoked. In context—and in his other programmatic discourse of 11 October 1962 (Gaudet Mater Ecclesia)—this means a “pastoral” aggiornamento, not the solemn reaffirmation and defense of doctrine against modern errors.

From the perspective of unchanging Catholic theology, several grave problems appear:

1. Pastoralism against Dogma.

– The notion that the Council’s primary task is to adjust language and approach to modern man, without explicitly reaffirming the condemnations of the Syllabus, Lamentabili, Pascendi, Quas primas, and others, implicitly relativizes those magisterial acts.

– St. Pius X anathematized precisely the idea that dogma must be “adapted” to the modern conscience or that pastoral practice could contradict defined doctrine. To reframe the Council as a massive pastoral public-relations exercise is to subordinate truth to utility—formal Modernism.

2. Implicit Denial of the Social Kingship of Christ.

– He speaks of the Gospel “penetrating civil culture,” but omits that civil authority has the duty to recognize and publicly worship Christ the King, as Pius XI solemnly teaches: peace is possible only when individuals and states submit to His reign (Quas primas).

– By adopting language of cultural permeation without asserting Christ’s legal and political rights over nations, the allocution aligns with the condemned thesis that “the Church ought to be separated from the State, and the State from the Church” (Syllabus, 55).

3. Horizontalizing the Marian Role.

– The Immaculate Virgin is invoked as “Mother of God and our Mother” to help them so that their ministry may be fruitful in making the Gospel better known and diffused. This sounds pious, but her unique role as Vanquisher of Heresies and Terror of Demons is eclipsed; she becomes patroness of a conciliar pastoral program rather than Queen who demands conversion to the one true Church.

– From an integral Catholic perspective, Marian invocation divorced from the combat against error and sin is sentimental exploitation; it attempts to sanctify a revolution with traditional symbols.

4. Collegial Flattery vs. Petrine Authority.

– The speech continually emphasizes “we with you,” “your collaboration,” “your merits,” “fraternal joy.” This flattering language prefigures the doctrinally problematic collegiality that undermines the monarchy of the papacy as defined by Vatican I.

– True Catholic teaching (Vatican I, *Pastor aeternus*) asserts that the Roman Pontiff has full, supreme, immediate jurisdiction over the universal Church, not as a coordinator of episcopal democracy, but as Vicar of Christ. John XXIII’s rhetoric is that of a democratic moderator of an episcopal parliament—precisely what St. Pius X warned against when condemning the democratization of the Church.

5. Absence of Anathema.

– Ecumenical councils, in Catholic tradition, solemnly define dogma and condemn errors. Here, at the conclusion of the first session, there is not a word of condemnation—only celebration.

– This omission is not incidental; it signals the principle later enshrined by the conciliar sect: a “pastoral” council without anathemas, a rupture from the perennial form of the Church’s magisterial act. A council recoiling from anathema voluntarily lays down its arms in the face of heresy.

Symptomatic of the Conciliar Sect: From Militancy to Self-Referential Humanism

The allocution is a pure distillate of the mentality that would soon produce the new religion.

Consider its underlying assumptions:

– The world is not portrayed as a realm in revolt against Christ and His Church, enslaved to Freemasonry and naturalism, as Pius IX so lucidly describes, but as an audience expecting “spectacle” and “hope.”

– The gathered bishops are praised not as guardians of an objective, handed-down doctrine, but as a kind of world senate engaged in “studies” and “formulas” to render the Gospel more acceptable to contemporary man.

– The mission of the hierarchy is reimagined: not primarily to rescue souls from eternal damnation through preaching, the sacraments, and discipline, but to ensure that Christ’s message “penetrates civil culture” in peaceful cohabitation.

This is the embryo of:

– the cult of “dialogue” replacing mission;

– religious liberty in the liberal sense replacing the doctrine of the one true Church and the duty of the State to profess it;

– ecumenism replacing the call to conversion of heretics and schismatics;

– the “people of God” ending the visible juridical clarity of the Church as a perfect society.

All this flows naturally from the attitude displayed here: no enemies denounced, no errors condemned, only mutual congratulations, shared emotions, and a worldly-friendly “joy.”

The Syllabus identifies as an error the proposition that “the Roman Pontiff can and ought to reconcile himself with progress, liberalism and modern civilization” (80). Yet John XXIII’s entire tone is an overture to precisely such a reconciliation. The “spectacle” of the Council is offered to the world as sign that the Church is ready to adapt, to renounce her alleged “severity,” to cease condemning and start affirming. In other words: to abandon her divine constitution.

The Inversion of Authority: From Teaching Church to Listening Church

The speech thanks the bishops because “through you… the voice of all Catholics has been in some way heard by us.” This is a subtle but deadly inversion.

Catholic doctrine, articulated in Lamentabili and Pascendi, rejects the modernist thesis that the teaching Church merely expresses the religious sense of the faithful, the “experience” of the community. It is the hierarchy that teaches; the faithful receive. The Church is docens (teaching) and discens (learning); the direction is from Christ through the hierarchy to the people, not from the people to Christ via the hierarchy.

By presenting himself as listener to the “voice of all Catholics” expressed through the conciliar assembly, John XXIII adopts the condemned modernist ecclesiology in which revelation continues in the consciousness of the people and the magisterium merely ratifies it. This is exactly the spirit Pius X anathematized: doctrine evolving from below, dogma as expression of common consciousness.

Thus, a few phrases of courteous flattery encode a revolution in authority: the usurper presents himself as moderator of a listening process rather than supreme teacher demanding submission to defined truth.

Strategic Omissions: The Loudest Accusation

Measured against the integral Catholic faith, what this allocution does not say is the most damning:

– No invocation of previous solemn condemnations of liberalism, rationalism, indifferentism, socialism, naturalism, ecumenism, Modernism.

– No reaffirmation that “outside the Church there is no salvation” must be believed as the Church has always understood it.

– No reminder that bishops must defend their flocks from heretical teachers, false mystics, and Masonic infiltrators.

– No call to penance, reparation, or Eucharistic adoration as remedies for contemporary apostasy.

– No warning against the enemies within—modernist theologians, biblical subverters, liturgical revolutionaries—whom St. Pius X identified as wolves in the sheepfold.

Instead, we hear of “joy,” “spectacle,” mutual compliments, and the desire that the Gospel enjoy better access to “civil culture.” This is precisely the naturalistic humanitarianism later weaponized to justify the profanation of the liturgy, the disarming of doctrine, the glorification of man, and the replacement of the Most Holy Sacrifice by an ecumenical meal-rite.

In continuity with authentic pre-1958 teaching, the conclusion is inescapable: this allocution is not a benign ceremonial text; it is a programmatic manifesto of capitulation. It reveals a mentality incompatible with the Catholic notion of a Council, with the prerogatives of the Roman Pontiff, and with the militant vocation of the Church.

Contrasting with Quas Primas: Christ the King or Cultural Chaplain?

Pius XI in Quas primas teaches that the principal cause of the world’s miseries is the rejection of Christ’s reign in private and public life, and he instituted the Feast of Christ the King precisely to reassert:

– Christ’s absolute sovereignty over individuals, families, and states;

– the duty of civil rulers to submit legislation and public life to Christ’s law;

– the incompatibility of secularist “neutrality” with God’s rights.

He explicitly condemns laicism and recalls that only the reign of Christ can restore peace.

Set this luminous doctrine against John XXIII’s tone. He wants the Gospel to “penetrate civil culture”; he does not demand civil culture’s submission to Christ the King. He stages a “spectacle” for the world to admire, instead of warning the world that Christ will come as Judge and King, that nations will be judged for their laws and apostasies.

Pius XI arms the Church with a feast to condemn public apostasy. John XXIII inaugurates a council in which condemnation becomes taboo. The result, inevitably, will be the enthronement of man where Christ must reign: the cult of human dignity, religious liberty in the Masonic sense, ecumenism that denies the unique rights of the true Church.

Quas primas is thus a powerful doctrinal weapon exposing the betrayal implicit in this allocution. What Pius XI declared necessary, John XXIII effectively suspends. The path from here to the abomination of desolation in the sanctuary—neo-rites, blasphemous “liturgies,” public acts of interreligious idolatry—is straight.

Fruit of the Same Root: The Conciliar Sect Unmasked

Seen retrospectively, this address is not an isolated courtesy; it is a precise snapshot of the new religion as it emerges:

– A religion of “joy” without fear of God;

– of “unity” without doctrinal clarity;

– of “spectacle” without sacrifice;

– of “pastoral” concern without dogmatic obligation;

– of “listening” and “collegiality” without monarchic authority;

– of “penetrating culture” without commanding kings and nations to adore Christ.

This mentality will issue in:

– the destruction of the traditional Roman Rite and its replacement by a man-made rite;

– the practical abandonment of the Syllabus and of Lamentabili;

– the assimilation of liberal “human rights” as quasi-dogma;

– the neutralization of missionary zeal and its replacement with syncretistic dialogue;

– the enthronement of the world’s approval as ultimate tribunal.

The allocution’s gentle tone and harmless phrases are, theologically, more dangerous than open persecution: they seduce bishops and faithful into believing that to cease condemning is charity, that to adapt is pastoral wisdom, that to please the world is evangelization.

But the authentic Church, as taught unwaveringly until 1958, cannot renounce her militant, exclusive, dogmatic character without betraying her divine constitution. Veritas non mutatur (truth does not change); anathema sit (let him be anathema) is not a museum piece but the living defense of revealed truth.

Therefore, judged by the standard of that unchanging doctrine, the address of 7 December 1962 stands as a concise manifesto of theological and spiritual bankruptcy: the abdication of the papal office’s essential functions, the reduction of a council to public relations, and the inaugural bow of the conciliar sect before the world it should convert or condemn.

Source:

Allocutio in XXXVI Congregatione Generali ad Patres Conciliares in Vaticana Basilica adunatos, d. 7 m. Decembris a. 1962, Ioannes PP.XXIII (vatican.va)

Date: 11.11.2025