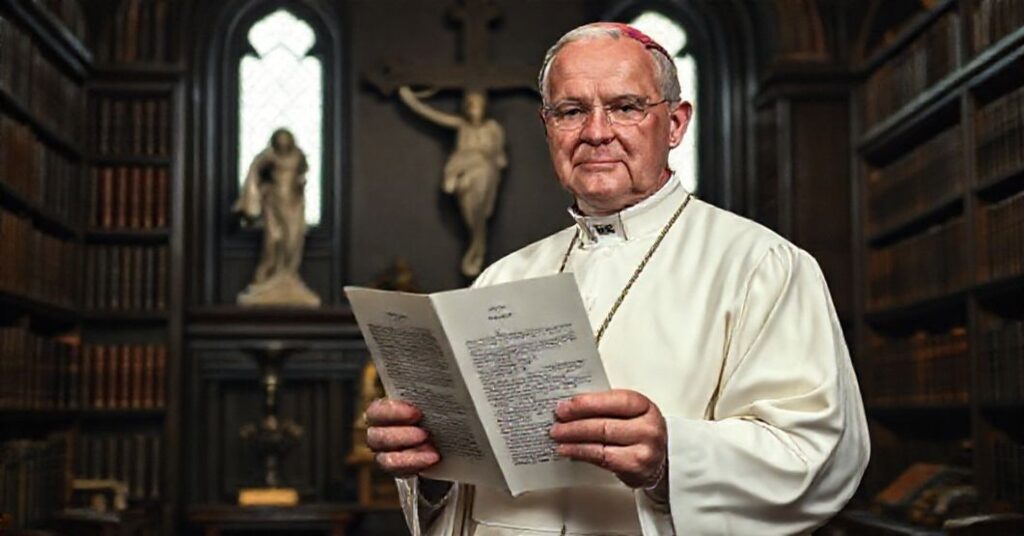

PIAE CUM CERTATIONE (1962.02.19)

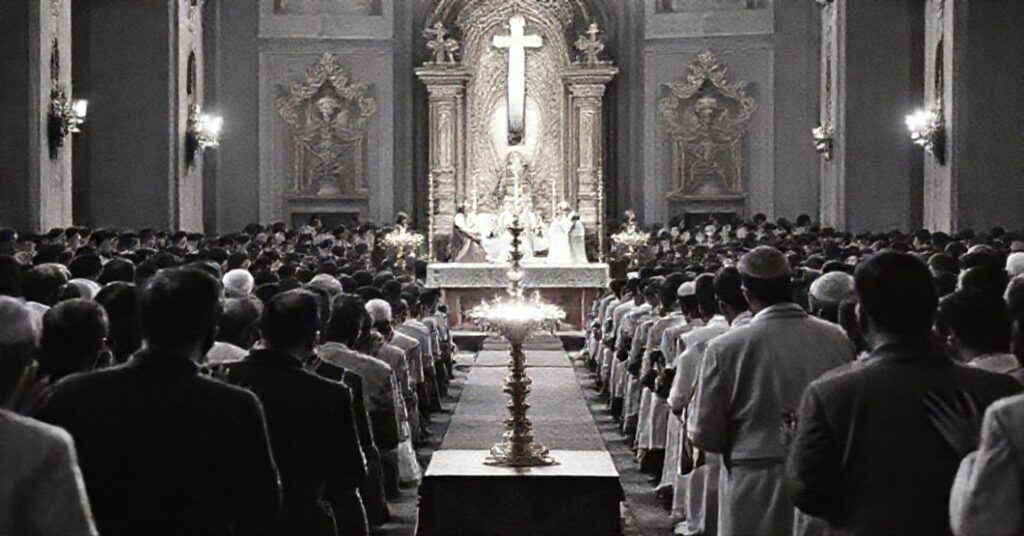

A brief Latin letter of John XXIII (Roncalli) congratulates Antonio Caggiano, “cardinal” and archbishop of Buenos Aires, on fifty years of priesthood, praising his diocesan administration, his role in organizing Eucharistic and Marian events in Argentina, his work with “Catholic Action” and “social action,” his mediation in a railway dispute, and granting him the faculty to impart a blessing with plenary indulgence on a chosen day; the entire text is one smooth, courtly panegyric which, by its silences and euphemisms, reveals a program of ecclesial naturalization and the consolidation of the conciliar revolution within Argentina’s hierarchy.